Again, I am sharing an MFA annotation here, which is not exactly a review, but should tell you what I thought of the book, in addition to my thesis about cinematic structure. Since I labeled this a review, though, I’ll start with what I wrote on Goodreads:

This is a very difficult and important book. I wasn’t sold on some of the finer points of characterization at first, and I had to take breaks after a few graphic/disturbing scenes, but by the end I couldn’t put it down and had tears in my eyes. READ THIS BOOK.

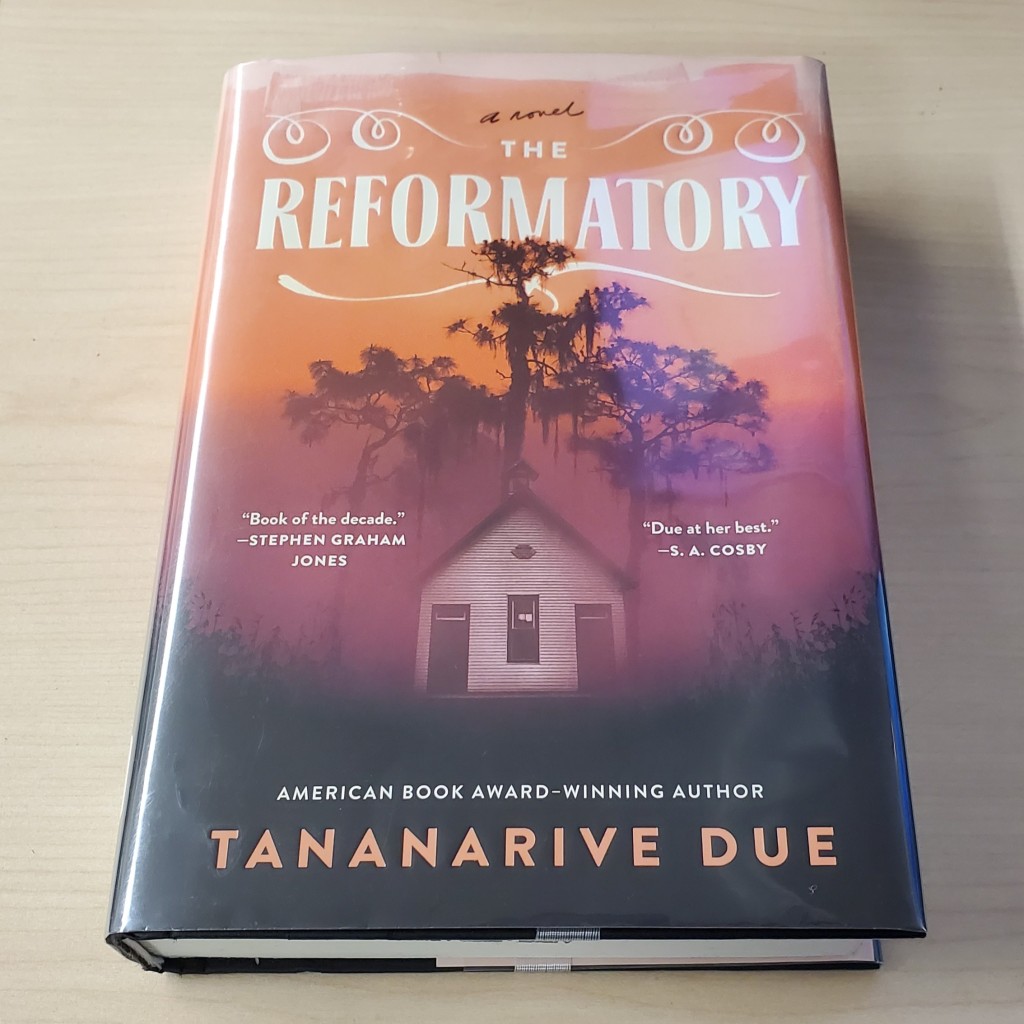

Cinematic Structure in The Reformatory

Reading Tananarive Due’s 2023 novel, The Reformatory, one can tell the author has a background in screenwriting. In the book, Due uses her own family history to inform the fictionalized documentation of what happened at the real Dozier School for Boys in early-to-mid-20th century Florida, and infuses the story with ghosts and hoodoo to amp up the entertainment value. The Reformatory is an important work in its own right—equal parts moving and disturbing—but its success as a work of fiction that is commercially ready to be adapted into a film lies in its adherence to cinematic structure.

The Reformatory is sectioned into eight parts, rather than Hollywood’s usual three for screenplays, but a close examination of the page count at key moments in the story shows how much Due must have considered standard dramatic formula in crafting her novel. Considering Blake Snyder’s 15-beat structure, the “Opening Image” is a given, and the “Set-Up” is somewhat flexible, so every story will hit those marks fairly easily (assuming the Set-Up isn’t too long). So the real test is whether the writer can hit a few essential marks: the inciting incident or “Catalyst,” the three act breaks, the midpoint, and the “All Is Lost” moment before the start of Act Three/The Finale.

Regarding the Catalyst, The Reformatory delivers a little early, bringing the protagonist, Robbie Stephens, to The Reformatory on page 43. This is 7.5 percent of the way into the novel, compared to Snyder’s ideal 10-11 percent for movies. However, this event starts Chapter 5, which falls right on the target 11 percent mark (there are 43 chapters total). In many ways, Robbie kicking Lyle McCormack and Red McCormack finding out about it in Chapter 1 (Due 13) feels like an inciting incident, because it’s what causes him to be sent to The Reformatory, but as the bulk of the story occurs at and is centered on The Reformatory, we can consider this just part of the necessary Set-Up.

Then we have the first act break on page 125, at the start of Part III, when Robbie is sent to the “Funhouse” with his best friend, Redbone, for allegedly talking about escaping. This happens at roughly the 22 percent mark, compared to Snyder’s 20 percent, but is again close enough to count. The “B Story,” though perhaps less critical, is pretty far from the target 22 percent, occurring at about 33 percent in Chapter 15, at the beginning of Part IV: this is when Robbie’s older sister, Gloria, pursues justice for him via her employer’s lawyer friend. Though the friend basically says she can’t help, her employer, Miss Anne, agrees to pay for a lawyer if Gloria can find one. This is definitely the B story in my mind because it shows a divergence between Gloria and Robbie in their thinking as far as how to get Robbie out of the Reformatory. Where she doubles down on her belief in legal means, Robbie accepts he may have to run away on his own.

The Midpoint, though, is the strongest example of Due’s adherence to cinematic structure in the novel, as it clearly occurs right in the middle of the book, at 50 percent of the novel’s page count, in Chapter 22: Superintendent Haddock offers Robbie early release from The Reformatory and no more trips to the Funhouse for him or his friends if he’ll catch “haints,” or ghosts, for him (284). At the end of this chapter, on page 288, Robbie has the chilling realization that his and Redbone’s friend, Blue, is in fact the ghost of a boy named Kendall Sweeting. This is a huge moment for Robbie, who now has to choose between his living friends and his dead ones, which may or may not have moral consequences (in part because Robbie doesn’t know if the catching the haints will harm them in some way). The stakes have definitely been raised, Robbie has experienced a kind of “false victory” in receiving the offer of early release, and the proverbial clock is now ticking, since Haddock will expect him to catch a haint every day now, and the more he delays, the more his freedom is in jeopardy. For Snyder, these are all necessary elements of the Midpoint.

The next important beat is the “All Is Lost” moment, which for Snyder occurs at the 75 percent mark, and for Due occurs in The Reformatory when Redbone dies in Chapter 33, at the 77 percent mark. On page 443, Robbie realizes that Redbone has been killed by another boy, Cleo (who had bullied Robbie when he first arrived at The Reformatory), at Haddock’s behest, when Robbie and Redbone failed to catch a haint they promised to bring in. By this point, Gloria had given up on freeing Robbie by legal means, and had gifted him with an escape plan (374) that Robbie planned to include Redbone in (382). With his best friend murdered, Robbie’s desperation grows, but so does his resolve to escape; even if he must rely on the somewhat traitorous Blue to help him.

Finally, we break into the third act on page 484, about the 85 percent mark, in Chapter 37, when Robbie begins his escape. It’s a little off Snyder’s 80 percent target, but not noticeable in the reading of the novel, as the final act (and really, the whole second half of the book) is utterly engaging. Due’s finale has Robbie stealing the haint jar from Haddock’s office; crossing the campus while everyone is distracted by a kitchen fire set by Blue; and making it to the creek on the other side of the fields to release the haints, only to be caught by Haddock and Crutcher (a black Reformatory employee and brother to Robbie’s music teacher). Gloria comes to the rescue with a gun, but misses Haddock, who is killed by his own dogs, under the influence of the freed haints.

Looking at the structure of The Reformatory through a cinematic lens is helpful to understand how important and useful Snyder’s beats are in crafting an engaging story, whether in the form of a book or a script, or likely many other forms of storytelling. Although the screenplay I’m working on is not an adaptation, analyzing Due’s novel with Snyder’s beats in mind shows me how flexible (or inflexible) I can be to maintain appropriate pacing and hit key moments at the right time in the script. Hopefully this is a helpful illustration for other screenwriters as well.

Works Cited

- Due, Tananarive. The Reformatory. Saga Press, 2023.

- Snyder, Blake. Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need. Michael Weise Productions, 2005.

P.S. The blurb/excerpt for this post that you see on the blog home page was written by WordPress’s AI generator.

I am 1/2 way thru the book, and it’s taking longer than usual, because I’m thinking of the characters and I just want their pain to stop. It’s like I know them, I want them to be safe. This is like a Stephen King book, in that I “know these people”, they are so well described. I’m hooked. This is all gut wrenching, they are only children I keep saying. Like Gaza, just little kids.

LikeLike