Maybe we can make “Theater Thursday” a thing??

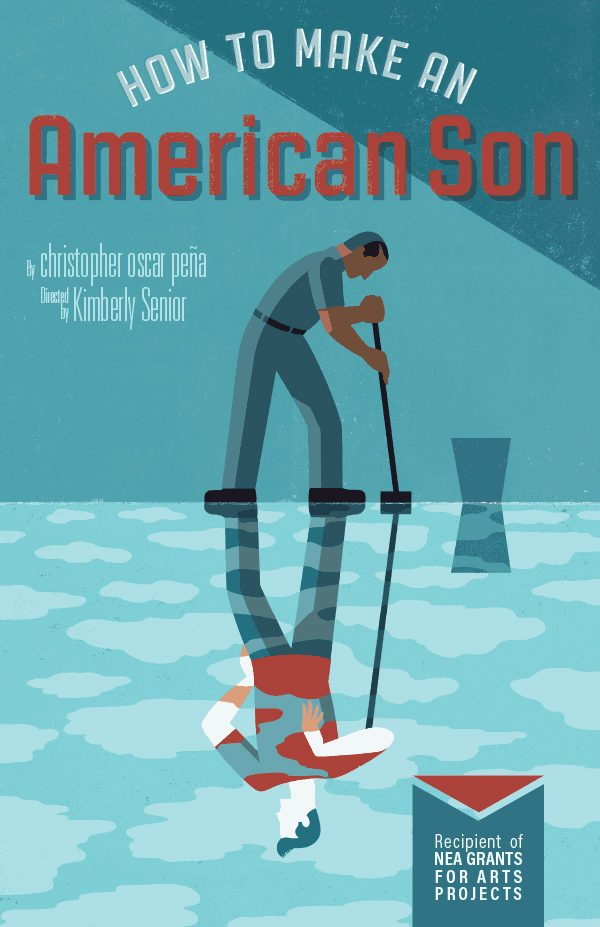

Here’s my last annotation of the term, on Christopher Oscar Peña’s new play, how to make an American son.

The experimental immigrant story of how to make an American son by Christopher Oscar Peña has a lot to teach us as people, but also as playwrights and screenwriters. While the formatting and lack of punctuation does take some getting used to, Peña’s pages upon pages of uninterrupted dialogue prove how little written direction is needed to create an effective scene —or conversely, how much can be conveyed without explicit direction.

After a flowing page of stylized description to set the scene, Peña provides another full page of straight dialogue between Mando—a “white looking (fair skinned) immigrant latino with an accent / dressed in a suit and tie”—and his son Orlando: “a fifteen-going-on-sixteen teenager / …[who] / looks and sounds white / gay” (Peña 3). Other than that, all we know is that Mando owns a maintenance company, that none of his certifications “are education based / or from educational institutes,” that he “is scolding his son,” and that “there is a piece of paper between them” (3). Then Mando speaks:

okay

and what about this one

on july 15th

for

wow

one hundred and eighty four (4).

Here, as throughout the play, the line breaks serve as punctuation or pauses, and even though we come in in the middle of their conversation, it’s so clear what’s happening in the scene. We can tell a practical father is confronting his son about a charge for something that costs too much (i.e. more than he expects). We can see the father peering at the receipt, hear the judgment in his “wow.” Then, after a brief back-and-forth in which it’s determined Orlando has spent all that money on books from Barnes and Noble, the humor comes to a head and enhances what we already know about these characters: Orlando says, “what do you have against reading / i could be out buying drugs / … i swear youre the only parent who complains that his kid is buying books,” to which Mando responds, “you’ve never heard of a library / other parents send their kids to libraries” (4). Peña doesn’t have to add direction here for us to see these characters throwing their hands up or to hear the sass in their respective voices, because the argument is familiar; even if we didn’t grow up with a frugal parent, the scene resonates because it’s relatable, and excess direction would disrupt the rhythm and jeopardize that resonance.

Near the end of the play, in the “dads” scene, we can again see how important the flow is to the feelings that are evoked and to our understanding of the characters. The scene begins with Mando conversing with longtime client Richard “Dick” Hinkle about the confusing origin of his nickname (79), and transitions into a discussion/commentary on the positions of the two men. Dick says “its just the way it is,” but we know he’s talking about more than his name, just as we do when Mando says “somethings will never make sense to me” and Dick responds, “I guess they won’t.” Right after that moment, we see the rare stage direction that “dick inspects the glass,” which perfectly but subtly notes the shift toward a “new” topic of conversation: Mando’s contract with Dick’s company. Only what the conversation really does is show us that Dick is aptly named, and that no one who could afford to stop working with him would stay. Dick says, “you[r] competitors / theyre very aggressive / their prices were better-” and while Mando interjects with “but not the quality,” as we too, might be led to believe, Dick ignores him and carries on with “but i know how important this account is to you / and that means something to me / so / i want you to know i went to bat for you” (80-81). As if Dick were truly doing Mando a favor! While, once again, we can picture the body language of the characters in this scene from the words and line breaks alone, we can also better feel the difference between what comes before and after “dick inspects the glass”—before the direction, we might believe that Mando and Dick’s banter shows only ignorance on the latter’s part, but after, we can see that Dick values his power and position more than any genial relationship he might have with his contractor, and is purposefully contributing to the socioeconomic gap between them.

There’s much more that could be illustrated by further examples of Peña’s unpunctuated dialogue, but hopefully the evidence presented above is enough to give the reader a taste of how to make character traits and emotions come through clearly without an excess of direction. As a screenwriter who has been told she sometimes “over directs” in her script writing, I found Peña’s play to be illuminating in this regard, and will endeavor to cut back on my action lines for the sake of more impactful and nuanced dialogue.