For this week’s “Movie Monday,” I revisit a 2010 film written by David Siedler, who sadly passed away two months ago. It’s the only writing project of his I’ve seen, but it’s also his highest rated feature, for good reason.

So please enjoy this essay—my last film MFA annotation of the term—on one aspect of it:

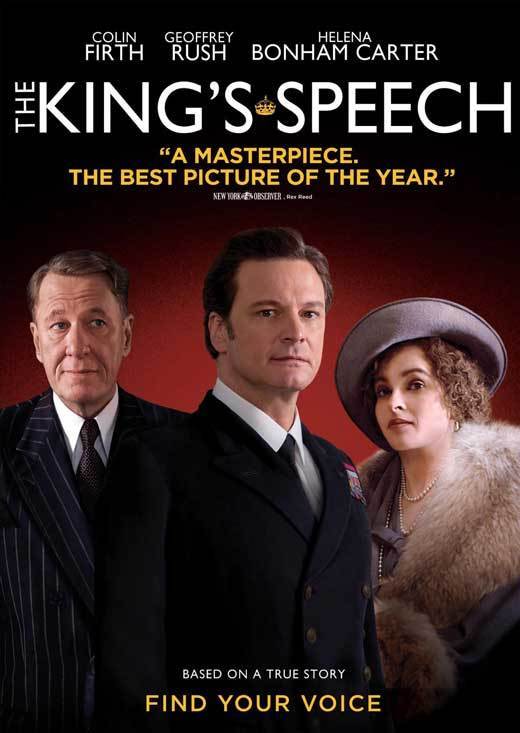

Subtext in The King’s Speech

On the surface, The King’s Speech is a simple “dude with a problem” story: a man is forced to surmount the mental and physical obstacle of his almost lifelong speech impediment by being thrust into a position of power which requires public speaking. But there’s more to it than that, and not just because the main character will become King George VI, who assumed the throne just before World War II began. This story is laced with subtext that explores friendship, family, and fealty, making this a layered film worth studying.

At the beginning of the film, our protagonist, the Duke of York—son to the king of England, “Bertie” to his family—is apparently at his wit’s end, having tried therapist after therapist to erase his stammer, to no avail. Not ready to give up, despite his insistence, Bertie’s wife Elizabeth employs Australian Lionel Logue to take on the case. Bertie continues to resist, but eventually meets with Lionel regularly and begins to make progress. After a particularly personal divulgence, Bertie tells Lionel he’s “the first ordinary Englishman I’ve ever really spoken to,” which Lionel interrupts to correct “Englishman” to “Australian.” Rather than acknowledging the correction, Bertie carries on about how the “Common Man” knows nothing of him, and him virtually nothing of the Common Man. Lionel responds with, “What’re friends for,” to which Bertie replies, “I wouldn’t know” (Siedler 46). While this may not seem particularly subtextual at first, there are a couple key things happening in this scene, which are not stated outright: Bertie’s failure to acknowledge Lionel’s correction about his identity shows both his insistence on the social gap between them and his denial of their differences. He views his association with Lionel as shameful, so he pretends Lionel is someone other than who he is (including an actual doctor). Bertie holds onto his prejudice about Australians as well as “the Common Man” even as he obliquely expresses his desire for understanding and some level of equality among them. He’s just divulged heart-wrenching details about his childhood to this relative stranger, and acknowledges it in this bit of dialogue, but he also distances himself from this person/the People, without coming right out and saying, “I’m better than you, despite my physical failings.” He’s not ready to admit that he needs Lionel, as both a “doctor” and a friend. Bertie’s statement that he “wouldn’t know” what friends are “for” indicates that, not only has he never had friends, but also that he refuses to view Lionel as a friend.

Bertie eventually comes around to appreciating Lionel, first on a professional level, and this shows in his presentation of the therapist to the archbishop, Cosmo Lang, as preparations are made for Bertie’s (reluctant) coronation. When Bertie introduces Lionel, the archbishop replies, “Had I known Your Majesty was seeking assistance I would’ve made my own recommendation” (70). While British people may see this less as subtext and more as simply how English people speak, the archbishop is nevertheless saying more than his words denote. Even on the page, we can hear the tone with which this statement is made, which shows the archbishop was not actually expressing his desire to be helpful, but his indignance at not being consulted (which is stated more explicitly later, when he tells Bertie “you did not consult, but you’ve just been advised” [75]). The archbishop is trying to pull rank on the new king of England, and continues his attempts to undermine him in protesting, “it shall be extremely difficult” to allow Lionel to attend, that the King’s Box is reserved for “members of your Family,” and that “The Church must prepare his Majesty,” rather than allow Lionel to prepare Bertie. Even as the archbishop caves to Bertie’s “wishes,” he still delays the speech therapist’s preparation until evening (71). Still, this exchange proves where everyone’s loyalties lie, and that Bertie views Lionel as someone worth vouching for, even to the point of defying the head of the church.

Although Bertie later finds out Lionel Logue is not actually a credentialed doctor but a graduate of the “school of hard knocks,” as it were, eventually they are friends again and working to cure Bertie of his impediment. At the end of the film, only Lionel is allowed into the recording room with Bertie to deliver a nine minute speech about preparing to go to war with Germany (again). However impossible this task may have seemed at the beginning of the film, once Bertie begins speaking, “[h]is cadence is slow and measured, not flawless, but he does not stop” (86). After the speech, Lionel says, “You still stammered on the ‘w,’” to which Bertie responds, “Had to throw in a few so they knew it was me” (88). It’s a truly heartwarming moment, which, while humorous, is also another way of showing that Lionel will be honest with Bertie, perhaps more than anyone else, and keep pushing him to improve. Bertie does eventually thank Lionel explicitly, but his statement that he messed up on purpose is its own “thank you,” Bertie’s acknowledgment of the progress he’s made and the fact that, in the end, Lionel was right: he could overcome his impediment, and he could be a king worthy of following in his father’s footsteps.

While there’s more that could be analyzed with regard to subtext in The King’s Speech—fathers’ relationships with their children could probably fill another paper—Bertie’s relationship with Lionel is really what drives the film emotionally. Yes, there are other films with more subtle subtext worth studying, but Siedler’s script shows that even a little subtext in the dialogue can go a long way toward making a more interesting film. It also gives me a better idea of how to craft English characters, who seem naturally inclined toward innuendo and the unsaid.

Work Cited

Seidler, David. The King’s Speech. Script Slug, 2010, assets.scriptslug.com/live/pdf/scripts/the-kings-speech-2010.pdf.