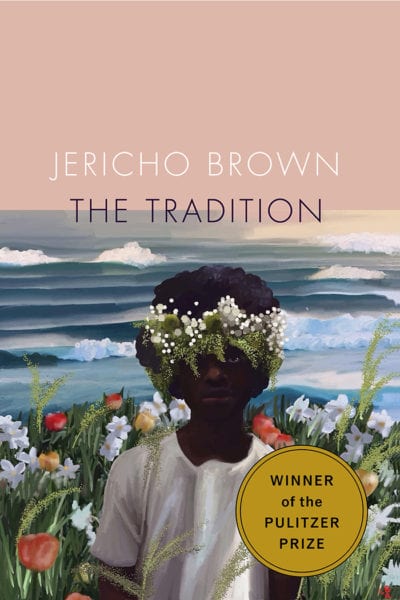

This post grew out of one of my first MFA annotations on Jericho Brown’s book, The Tradition: Civic Dialogue Edition, so I apologize if it comes off a little hodge-podgey. It’s kind of a review (I loved the book), but more of an analysis, and also a plug for small press. Mine is accepting queries this month, so check out our guidelines if you have a manuscript you’re looking to publish!

The Duplex: How Jericho Brown Maximizes Continuity in The Tradition

Jericho Brown’s Pulitzer-Prize winning book, The Tradition, is an unflinching expression of the poet’s views on love, violence, childhood and family relationships, and (in)justice on personal as well as national and environmental levels. The artfulness and accessibility of these poems—what I look for in poetry to be published by my company, Red Sweater Press—are enough to make this book award-worthy, but the way Brown ties the collection together is truly inspired. By examining the recurrence of his invented form, the duplex, throughout The Tradition, poets at any stage of their writing can learn how to put together a cohesive manuscript small presses want to publish.

If you’re not familiar with the duplex, it is a form sometimes referred to as a “gutted sonnet,” because it is 14 lines arranged in seven couplets. The lines “echo” throughout the poem, as the wording or meaning of each second line is slightly altered when it is repeated. This brings the reader to a new place at the end of the poem, without forgetting where they/the speaker came from, and what it took to get us to where we are in the present.

In a book so full of (justified) criticisms of people and the world we live in, it’s perhaps surprising that four of the five duplexes spread throughout The Tradition‘s three sections contain the word “love.” Yet in each of these poems, Brown also shows the reader violence, creating a sense of inextricability between these two concepts, both the result of strong emotions. But it’s not just the presence of the duplexes throughout the book that holds the collection together; it’s the narrative arc they create in their ordering.

The first “Duplex,” for example, paints the reader a picture of Brown’s adolescence, comparing the speaker’s “first love” to his father, who beat the speaker and likely his mother (Brown 18). The poem’s opening and closing line, “A poem is a gesture toward home,” sounds almost warm at the beginning, while at the end, it’s not quite sinister, but more darkly honest, illustrating something I think most readers experientially know on some level: families are difficult! We love them, but we also feel like we hate them sometimes, which Brown echoes in his On Being interview with Krista Tippett: “…all you got to do is have kids or a parent, and you actually do know what it’s like to feel like, ‘Oh, I could actually kill you…but I’m not, ‘cause I love you” (83).

The next “Duplex,” however, shows us how deeply the speaker has been wronged. This poem does not use the word love, but instead juxtaposes rape with “understanding / A field of flowers called paintbrushes” (27). Tippett describes this kind of conjunction as “where tenderness meets violence,” which Brown elaborates on by saying, “We put ourselves through huge inconveniences that are like certain kinds of violence, when we fall in love,” and that sometimes, “where love goes awry […] people use violence as an excuse for love” (83). In terms of narrative, this second duplex could be thought of as “the dark night of the soul” moment described in Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat beat sheet—the speaker is voicing his deep “hurt” and anger, his desire to “obliterate,” and the closing line (purposefully) fails to take on new meaning from the beginning; “The opposite of rape is understanding” is this stark reality that remains unchanged, for time immemorial (27).

The third “Duplex,” however, gives us more hope in its opening: “I begin with love, hoping to end there” (49). Interestingly, the page count between the second and third duplexes is the greatest between duplexes in this book; there’s quite a journey for the speaker who says “My body is a temple in disrepair” (27) to become someone who asks, “What are the symptoms of your sickness?” (49). In this third duplex, the speaker is taking the reader to account, as well as himself, in voicing what he doesn’t want or need: “I don’t want to leave a messy corpse” and “Some of us don’t need hell to be good” (49). There are multiple implications in these statements, but what works for the narrative arc is the poem’s increasing honesty with and confidence in the self, as well as the speaker’s boldness and action; he ends the poem by saying, “I grow green with hope” (emphasis added), rather than somewhat passively “hoping” he can live his life with love, or that the presence of love is all that is needed (49).

In the fourth “Duplex,” the speaker gains even more confidence, opening with the directive, “Don’t accuse me” (68). He recognizes that he “was too young to be reasonable,” along with his lover, but opposes this third party, calling them out for not doing their own due diligence to see what was really going on (68). Although infidelity isn’t exactly admirable, and no one likes excuses, this poem again illustrates the speaker’s growing comfort with the self and possibly past mistakes. The transformation and translocation of the lover in the last couplet highlights that of the speaker, too, although the lover’s is perhaps more of a criticism: “What’s yours at home is a wolf in my city,” a danger; and yet, the speaker feels justified: “You can’t accuse me of sleeping with a man” (68). The speaker refuses to have regrets, and lays claim to his own space.

This refusal of continuing to be damaged by the past is driven home in the final “Duplex: Cento.” Brown uses lines not only from his own poems, but the other duplexes themselves to show the reader where he’s been and how he’s come to understand his life. This final poem in the collection can be read as both a denunciation of the violence committed against black and gay men—“None of our fights ended where they began,” “Any man in love can cause a messy corpse,” “The murderer, young and unreasonable,” etc. (72)—and a recognition of the maturation of his understanding of love. The speaker is not forgetting, but moving beyond his past with his father and his hometown and becoming his own agent for change. If that’s not the perfect ending to a book, I don’t know what is.

To recap the journey of Brown’s speaker through these duplexes, one could simplify or summarize them thus: the speaker starts at home, where love is confused with violence; the speaker leaves home and experiences (arguably) even worse violence; the speaker develops a hopeful attitude toward future love, having persevered/survived; the speaker finds confidence in themselves and takes ownership of their actions in love; the speaker heals and moves on, while fighting for a future where other people don’t have to go through the same trials.

Though there are five duplexes, they are spread across three sections of the book, much like the standard three-act structure of a film. The last three duplexes appear in the third section, or what would be the third act of a movie, which makes sense, as the content of those three poems are finale-worthy movements toward self-actualization.

So, how does this relate to small press publishing? If you’re trying to find a home for your manuscript, one of the things you must remember is that, like the film industry, this is a business—as much as all us small press owners find inherent value in creative work, we have to sell books in order to keep doing what we love and bringing said creative work to the public. If you’re a published poet, you must know that poetry is a harder sell than fiction (and if you don’t, please do some research on the many reasons for this phenomenon), but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible or not worth doing. Still, if you want to write and publish a book of poetry that resonates with a wide-range of readers enough to make them buy a hard copy and recommend it to their friends, compiling the collection in a way that builds a narrative arc like Brown’s is a great way to hook readers and keep them engaged.

I’ve read probably 100 collections of poetry, published and unpublished (not to mention hundreds of individual poems) and I’ve noticed that the books with sections and narrative arcs of some kind are the ones I appreciate most. Like the most successful music albums (in my opinion), there should be a cohesion to the them. Some people are under the mistaken impression that, once they’ve written or published a bunch of individual poems, regardless of theme or style, it’s time to compile them in a book. While the connections between unrelated poems can and often has surprised people, including me with my own work, care must be taken to arrange them in a way that makes some sort of sense, even if poems take on new or initially unintended meanings in the context of the collection. You can put a poem about your family and a poem about environmental decay in the same book, but you owe it to yourself and the work(s) and your future readers to tie them together in some way. You can meander through different themes and subjects, travelling great distances from your point of origin, but we need to be able to follow some thread from the beginning to the end of your book. Repetition of a form is one way to do that, but it doesn’t have to be.

I suppose this is a long way of saying be intentional. Not every poem you write should necessarily go in a book, and not every great poem you write this year, for example, should necessarily go in the same book, or in the order that you wrote them. So carefully craft your poems, compile them in a relevant way, and editors, readers, and publishers will thank you. And, for the love of poetry, read, so you can see the possibilities, as well as what has worked in the past. Then submit!

P.S. If you’re thinking, ‘but wait! I want to be unique!’ remember this: you have to learn the rules before you can break the rules. Godspeed and good luck!