Horror-Comedy is apparently trending, and as long as it’s not too gory, I think I’m here for it.

In the last few weeks I’ve watched The Menu, Get Out, Nope, and for the second time, Parasite (I also watched Saltburn a few months ago, which definitely falls in the dark comedy category at least). My husband was the first to tell me comedy and horror go hand in hand, because it’s all about timing, apparently, but that’s perhaps another topic for a future blog post.

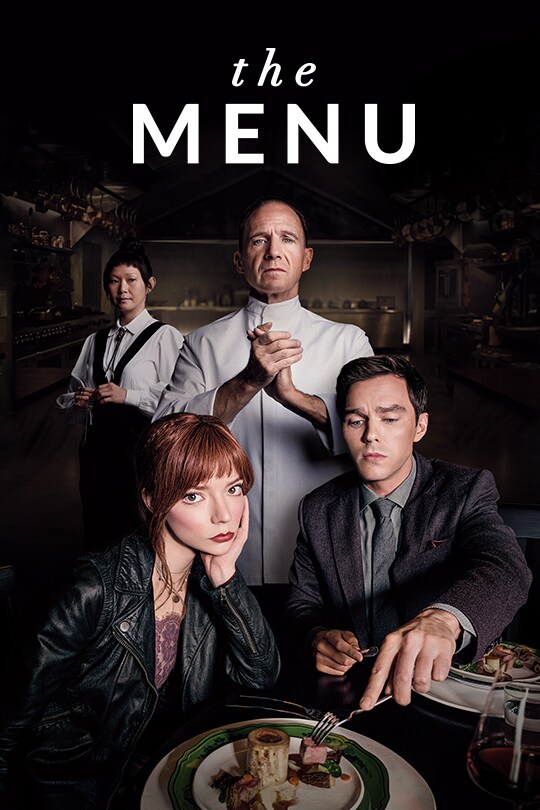

Below, please enjoy my MFA annotation on the structure of The Menu.

Breaking the Mold: How The Menu Serves Its Story

Anyone who has ever taken a film class or taught themselves to write a screenplay with a modicum of internet research should be familiar with the three-act structure employed in most commercially successful movies, and understand why it’s used: it works. However, more and more filmmakers seem to be looking for ways to make their stories stand out and push the boundaries of that structure, including writers like Seth Reiss and Will Tracy. The Menu is a great example of how to mix things up without losing the viewer or forgoing foolproof formula.

The Menu starts much like Rian Johnson’s Glass Onion (and many other murder mysteries before it), with the ensemble cast being ferried off to an exclusive island—a classic inciting incident for a movie in any genre, really (going to a new/remote location). Even the first act break comes on target, when the meal begins, but this is also where Reiss and Tracy seems to break the mold: for the rest of the film, the plot follows the literal form of an 11-part menu, which starts with amuse bouche (essentially an appetizer) and ends with a final dessert course. I say “seems to” because, upon closer inspection, one can see that each of the courses more or less line up with Blake Snyder’s 15-beat structure, which operates within the framework of three acts.

After the first course (appropriately titled “The Island”) comes the breadless “Bread Service,” during which the B story is revealed. Beginning on page 33, Chef Slowik literally tells the audience (in the restaurant and beyond the screen) a story, one of perpetual class struggles and systematic problems: “you, my dear guests,” he says, “are not the common man. So tonight you get no bread.” Here we see not only the kind of people the characters are (especially based on their reactions to not getting some of the chef’s famous bread), but also what Slowik’s motivations are; this is about more than just the people in the room.

The second course, “Memory” covers the “Fun and Games” or “Promise of the Premise” section, solidifying our understanding of the characters and hinting at the violence to come, which we expect from a thriller/horror movie. The third course, “The Mess,” brings us to the start of that onscreen violence and the official midpoint when one of the sous chefs shoots himself dead (54) and one of the guest’s fingers is cut off by another cook when he tries to escape (57). This whole sequence again accentuates character development as well as plot, showing us who is definitely irredeemable—Lillian Bloom, the food critic who thinks it’s all “theater” for her, and Tyler, who continues to enjoy his food without protest (55-57)—and who is getting a wake-up call—Margot, who realizes she might be the only sane person there, and the Movie Star, who’s starting to admit his lies (57).

After the midpoint of course comes the “Bad Guys Close In” period, which corresponds to the fourth course, or “palate cleanser.” During this sequence, Slowik drops the bomb that “none of us are getting out of here alive” (62), and he has his angel investor, Doug Verrick, drowned outside the restaurant (67), severing the “tech bros” last lifeline, and maybe everyone’s hope for escape. This is also when we learn the truth about Margot, and see her soften Slowik, creating “the slightest opening in his chain mail” (71).

Then, “All is Lost” in the fifth course, “Man’s Folly.” Here, Slowik reveals his own shortcomings (or rather, they’re revealed for him by another of his sous chefs he wronged), and sets the remaining cooks on all the male guests, who have been let out of the restaurant to run around the island in a darkly hilarious bid for their lives (74). It’s literally the “Dark Night of the Soul” for the men trying to escape, while the women get to sit inside and “enjoy” another course together, complete with the bread their boys were denied (75-77). (This only occurs in the script, and was cut from the film version, I imagine, because it might imply that women somehow deserve more privilege or leniency than men, just by virtue of being female, though Slowik clearly believes that men should pay for what they’ve done to women throughout history, regardless of their specific “sins.”) But the women aren’t totally off the hook, as their supervising sous chef, Katherine, says everyone dying was her idea, and she’s “super proud of it” (78).

Then we come to the third act break and the first “supplemental course,” also known as “Tyler’s Bullshit.” The young foodie finally gets his chance to work with his idol and completely botches it, serving Slowik “under-cooked lamb” and “inedible shallot-leek butter sauce” (85). By this time, Margot has already learned that he hired her for the night knowing everyone was going to die (and as he tells us when Slowik asks why, “Because you don’t offer seatings f-for one” [82]). So when he hangs himself at Slowik’s request, no one is really sad or surprised.

In the script, the next course is not only misnumbered, but also a little much, and therefore cut from the film version. (In “Gone Nuts,” Felicity is forced to feed her nut-allergic boss, the Movie Star, all manner of peanut dishes, and Lillian Bloom is “waterboarded in a giant pail of the emulsion” [93] that she complained was “broken” on page 34.) Margot is out of the restaurant at that time anyway, searching for a barrel at Slowik’s request, which is also when she enters his cottage and fights with his right hand, Elsa, who forces Margot to stab her in the throat (94). This is all part of the finale sequence, so when Margot uses a radio in the house to call the coast guard for help, we start to think maybe they’ll all get away—but at this point, do we want them to?

When it’s revealed the “coast guard” is just another one of Slowik’s cooks (101), Margot pulls her trump card and asks for a cheeseburger, after a few short monologues about how she doesn’t like the food, he’s “taken the joy out of eating” (103), and she’s “still fucking hungry” (104). Slowik serves her what looks like “the best cheeseburger ever,” and when she asks to take it “to go” (106), he obliges—she’s free!

Then, for the final course, we get the s’more, complete with its morbidly funny recipe: “marshmallow, chocolate, graham cracker, customers, staff, restaurant” (110). After the elaborate construction of a wall-to-wall dessert, the restaurant goes up in flames, and in the movie, we end on Margot, sitting on the “coast guard” boat from earlier, finishing her cheeseburger by the light of the fire. While The Menu does adhere to standard filmmaking structure, Reiss and Tracy have made the formula their own, and should be applauded for that. As a viewer, you don’t even really notice they’re following the formula, because you’re caught up in the menu, just as the guests are, and that immersion is a mark of great storytelling. Though I don’t quite have a corollary in my script, The Menu is instructive as far as how to use a somewhat external framework (like, in my case, the text of a poem) to structure one’s script in a unique and thematically relevant way.

Work Cited

- Reiss, Seth and Will Tracy. The Menu. Deadline, deadline.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/The-Menu-Read-The-Screenplay.pdf