I am tickled to be able to revive Movie Monday with my MFA annotations this term, which are all on screenplays!

Here’s the first of two for this month:

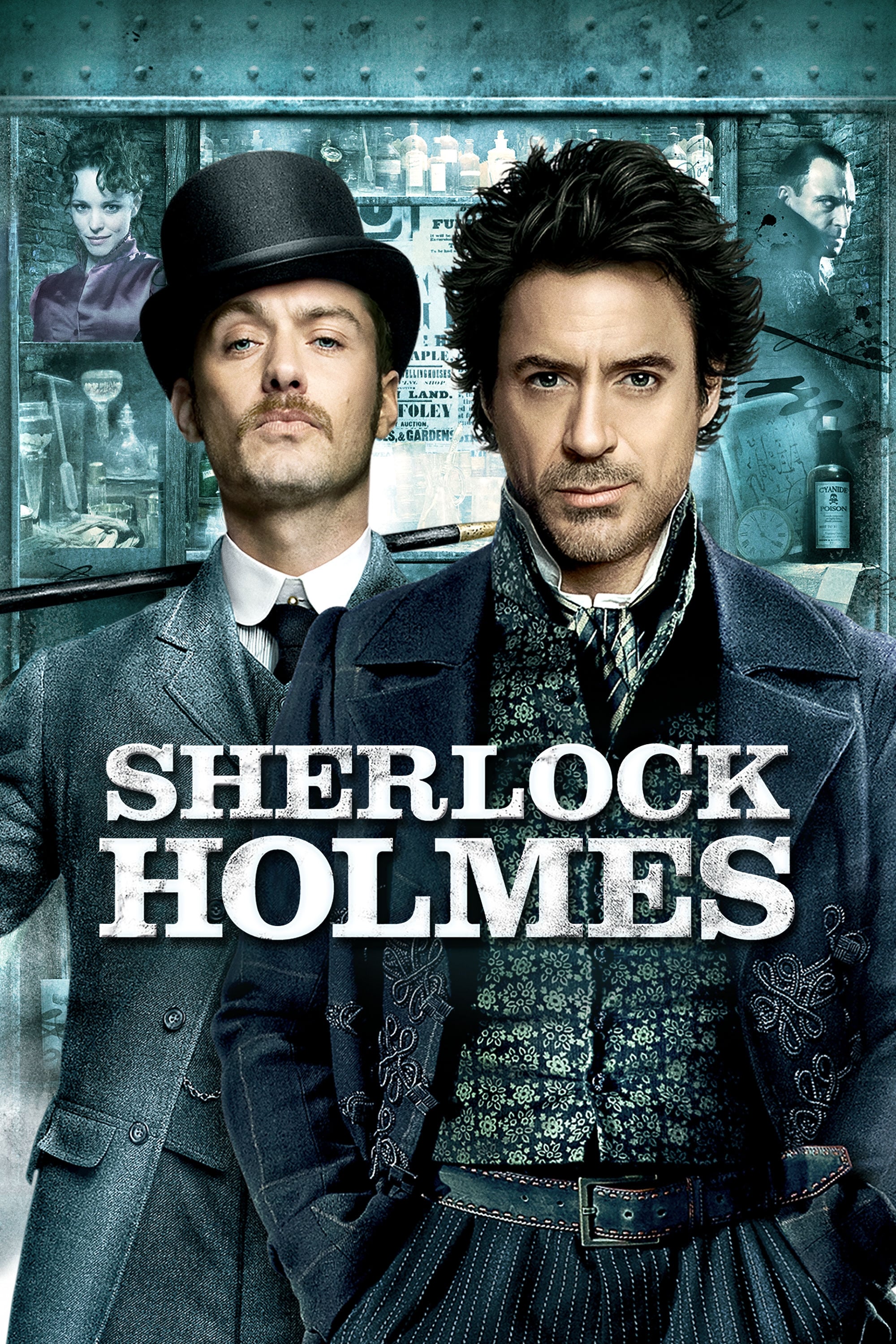

Characterization in Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes

While the director is usually the person who gets the most credit for making a film, and Guy Ritchie does lend his characteristic skill for facilitating quality banter to Sherlock Holmes, writers Michael Robert Johnson, et al. should be credited with making these classic characters leap off the page with new life. Readers (and viewers) need not know anything of Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation to appreciate the timeless relationship of a Holmes and his Watson, which in Johnson’s version is demonstrated in the shortest of dialogues and the sharpest of monologues.

In the film, the first words we hear are those in Holmes’ mind as he assesses his pursuer and prepares for a fight: “Head cocked to the left, partial deafness in ear. First point of attack…” (Holmes 1:42-1:47). This five-second sequence of words is enough to tell us the protagonist is analytical (“detail oriented”) to the extreme, an observer who probably has a lot of “on-the-job” experience (i.e. detective work) and unparalleled levels of perception. Then, when we see Holmes carry out his split-second plan to the letter and achieve his exactly desired results, we realize that he’s not only intelligent, but also physically capable. In just two minutes/pages, we know who the hero is and what skills he has to be the hero.

But Holmes, as we know, is not nearly as interesting without Dr. Watson. Just a minute later in the film (shortly after we’ve laid eyes on the villain, Blackwood, who really requires no characterization beyond a black robe and some Latin chanting at this point), Watson appears to thwart yet another thug pursuing Holmes. While this “rescue” on its own is not enough to convince the viewer Holmes needs Watson, the following exchange is enough to clue us in: Watson indicates that Holmes left his revolver at home, to which the detective responds, “Knew I’d forgotten something. Thought I’d left the stove on,” and Watson replies “you did” (Johnson 5). These three lines, while humorously “trivial” in the face of their circumstances—creepy wizard statesman performing some ritual that we assume ends in human sacrifice—also quickly illustrate Holmes’ mix of absent-mindedness and misplaced priorities, which without Watson’s particular brand of pragmatism might get him into trouble—even killed. We also get the impression that Watson is used to cleaning up Holmes’ messes.

While the aforementioned aspects of these characters continue to be refined with almost every conversation they have (with each other and others), Holmes’ response to Watson’s engagement is key. Before we’re even 10 minutes into the film, we know that Watson has a serious relationship with a woman which is causing him to leave Holmes’ home, at the very least, and that Holmes is likely to sit in the dark and go to ruin without Watson or a case to drive him out of the house and into conversation with people other than himself. At the 11-minute mark (page 15 of the 2nd Yellow script), Watson invites Holmes to dinner and they engage in a back-and-forth of one- and two-word lines that play out perfectly on screen:

WATSON: [So] you’re free this evening.

HOLMES: Absolutely.

WATSON: For dinner.

HOLMES: Wonderful.

WATSON: The Royale.

HOLMES: My favorite.

WATSON: Mary’s coming.

HOLMES: Not available.

This exchange is not only hilarious, it quickly illustrates how sour Holmes is on the whole idea of Watson leaving him for a woman. But the fact that Watson has not actually proposed to Mary at this point should not be lost on the reader (or viewer), as it illuminates the glaring co-dependence of the main male characters.

The dinner scene itself, however, is what clarifies Holmes’ biggest flaw and difference between him and Watson. When Mary “insists”—“She insisted!” Holmes says with a twinkle in his eye (17A)—that the detective reveal everything he can tell about her after having just met her moments ago, he “instantly” nails almost all of it, to the point of her previous engagement. Here he makes a critical error, assuming Mary “broke off the engagement and returned to England for better prospects. A doctor perhaps,” which causes her to throw wine in his face and leave, saying, “I didn’t leave my fiance…he died” (19). Of course this upsets Watson as well, who follows Mary out, but Holmes seems to only partially register the faux pas, tucking into his meal alone (20). This whole scene shows us how Holmes can absolutely be analytical to a fault, forsaking human decency and compassion for the “facts.” Watson’s departure here shows he sides with Mary, of course, and also has his priorities in better order than Holmes. Furthermore, while Watson understands Holmes’s shortcomings, he’s also prepared to leave him, as much to try and teach Holmes a lesson as to move forward in his own life.

This film and script are packed with great writing like this that the actors took to beautifully, bringing a dimension to the characters that far transcends their roles within the plot of Blackwood taking over the world and the thematic debate of science vs. religion. As screenwriters, we should all aspire to create such likable and believable characters, whether our genre is action, mystery, comedy, or anything else. In my own work, I hope to be able to achieve such clear and immediate characterization through dialogue, without being too on-the-nose or overusing overt character descriptions in the action for context.

Works Cited

- Johnson, Michael Robert, Anthony Peckham, and Simon Kinberg. Sherlock Holmes. CineFile, 2009, www.cinefile.biz/script/sherlockholmes.pdf

- Sherlock Holmes. Directed by Guy Ritchie with performances by Robert Downey, Jr., Jude Law, and Mark Strong, Warner Brothers, 2009.