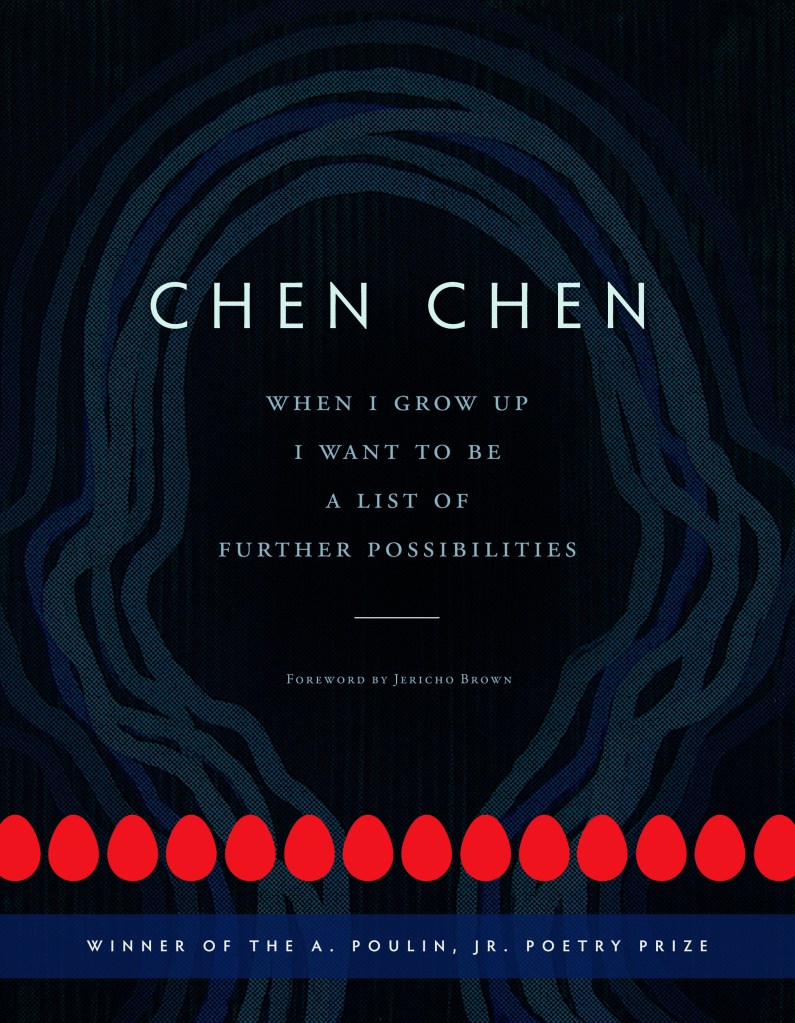

Time for another MFA annotation/poetry book review! I really enjoy Chen Chen’s work, and I’m excited to connect with him at our December residency in a few weeks. Although this book is a few years old now, I hope it continues to garner praise in the literary community for years to come. Learn more about him at: chenchenwrites.com

Exploring Further Possibilities for Play and Positivity in Poetry

Just from the title of Chen Chen’s full-length debut, seasoned poetry readers should be able to tell they’ve encountered a dreamer who isn’t afraid to do what they want. When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities is an important book for its passion and politics, but just as much so for its playfulness and positivity. With poems like “Self-Portrait as So Much Potential,” “I’m not a religious person, but,” and “Race to the Tree,” poets will surely find themselves inspired to write and be their fullest selves.

The collection starts with a playful prologue poem, or “proem,” as it’s been called: “Self-Portrait,” which situates the reader in the position of the speaker who is “Dreaming of one day being as fearless as a mango. / As friendly as a tomato” (Chen 13). The speaker isn’t trying to be deep or serious, but bringing in warm colors and juicy foods, items of comfort and splendor. He’s “dreaming,” but not naive, as he shows us his self awareness in the next lines: “Realizing I hate the word ‘sip.’ / But that’s all I do. / I drink. So slowly. / & say I’m tasting it. When I’m just bad at taking in liquid” (13). This casual, conversational way of writing is yet another indication that the speaker is unfettered by the pretentious side of poetry, which all too many students have seen and thought that’s all there is. In this poem, the speaker encourages the reader to throw out their assumptions or what they think they know and just ask themselves, who am I? What am I going to do? But this almost flippant way of writing does not negate the presence of art; after admitting “I’m no mango or tomato,” the speaker says, “I’m a rusty yawn in a rumored year. I’m an arctic attic” (13). While possibly not flattering, the juxtaposition of nouns and adjectives in that line is refreshingly original, and gives the reader a sense of dryness that connotes hunger and want, though not in an overly negative sense of lack; rather, it makes the reader feel like that same desire for more, and the belief that one can attain more for themselves, not out of selfish ambition but for self actualization.

In the next poem, “I’m not a religious person but,” the reader can see more of that self-actualization as the speaker firmly states his beliefs but also acknowledges the importance of keeping an open mind (and allowing himself to change it later if needed). The poem happily opens with humor, again: “God sent an angel. One of his least qualified, though. Fluent only in / Lemme get back to you. The angel sounded like me, early twenties, / unpaid interning” (17). The speaker goes on to describe being spoken to by “God,” and all the ways he tried to avoid conversation, only for “God” to end the conversation when the speaker asks about the afterlife. The irreverence here, rather than putting off the Christian poet, should be celebrated for its comedic honesty, which tells the truth of the speaker’s experience. Even as the speaker rejects whatever manifestation of God appears in this poem, he doesn’t completely discount its effect on or presence in his life: “I never heard from God or his rookie angel after that. I miss them. / Like creatures I made up or found in a book, then got to know a bit” (17). This closing tells the reader that there was some value in the experience, some more of the cosmic left to be discovered or understood. A pessimistic religious person might read this ending as “growing out of” God, but it could also be read as growing into a more mature spirituality—a graduation from the immaturity of a bargaining relationship indicated by phrases like “Stop it please, I’ll give you…” as well as “I tried to enrage God” and “I tried to confuse God” (17).

“Race to the Tree” is less humorous, but just as honest as the previous poem, and not without comedic effect. In this poem, the speaker details an adolescent escape from home in the night, in which he spends a few hours hiding from the police, whom his parents had called to locate him, after an argument about his sexuality. While in hiding, the young speaker dreams of kissing a boy, calls the biblical Eve Adam’s “ugly girlfriend,” and claims he’s evaded capture “using my spy & JV track skills” (21). The reader is likely to laugh here, then be quickly sobered by the description of an area “where my parents / put on their best American accents / & smiles, to earn degrees // the equivalents of which they’d already earned in China” (21). Even as it documents childhood trauma, the language of this poem finds its way into funny as well as sympathetic spaces, detailing relatable teenage attitudes as well as the injustices against his parents that may have contributed to the way they treated him. Amidst physical pain and pubescent suffering, the speaker still manages to motivate the reader toward positivity by encouraging others to stand up for themselves. So although this powerful poem may instill sorrow in the reader, it’s the kind that calls to action, rather than depressing into inaction.

As with all five-star poetry collections, When I Grow Up is a book of endless possibility and opportunity for education and inspiration. All poets, but especially those in need of permission to play and write freely, should read this book. Better yet, anyone interested in social justice and narrative poetry, as well as memoir in verse, should buy a copy of this book to help keep talented writers like Chen Chen writing and getting important books like his into readers’ hands.