This book was pretty out there; read on to see if it’s for you. My mentor posited the idea that Liu intentionally chooses references not everyone would know, and challenged me to consider why he might choose to be alienating; maybe you can answer that for me. At the very least, I plan to try writing a frankenpo!

As per usual, don’t steal my stuff.

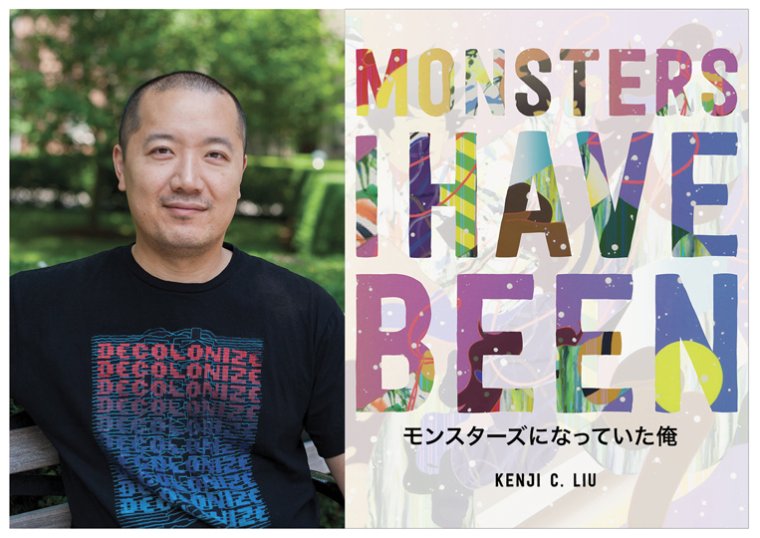

Frankenpoet: On Kenji C. Liu and His Monstrous Experimentation

Kenji C. Liu’s Monsters I Have Been is a wild ride through his denunciation of toxic masculinity and praise of gender fluidity. The method he uses to express these, however, is almost laughable in its strangeness; while shockingly original, it lacks a necessary accessibility in communicating its message(s) to readers. While Liu might be commended for his exploration of all that poetry can be, his use of devices like sheet music without staves and obscure references are simply too alienating to be effective.

Four poems in Monsters I Have Been incorporate music notes, starting with “Rajesh’s Theme,” which is entirely composed of music notes and musical instruction (Liu 18). While this piece cannot be accurately called a poem, it could be acceptable in a hybrid work if it were playable. Perhaps more accomplished pianists could determine the intended notes without a staff, but as it is printed without those lines, it’s much more difficult to play the song correctly. It is furthermore not easily discernible to the lay poet who Rajesh is, as the poem that precedes this one—“Rajesh Goes to the Stud Club”—is only said to be “after Qurbani,” an “Indian Hindi-language musical romantic action thriller film” from 1980, according to Wikipedia (there are no notes on either of these poems in the back of the book). Most readers of poetry are surely willing to look up an unknown word or reference here and there, but expecting one to conduct an internet search on a character from a 40-year-old Indian film to understand the voice of a poem that frankly comes off as a bit gross seems like too much to ask.

“Manifest Destiny for Sassy Choir” is the next musical poem in the collection, and also a “frankenpo,” which is essentially a poem of Frankenstein-ed texts. With these pieces, at least, Liu specifies the source material in the end notes, and this poem in particular is a combination of a 19th century manifesto containing the first record of the phrase “manifest destiny” and a transcription of Jimi Hendrix’s Woodstock performance of “The Star Spangled Banner” (94). However, the musical notations are once again too difficult to follow and apply to the words on the page, even while listening to a recording of the performance. (Plus, you have to turn the book sideways to read this one.) A reader can guess at what Liu is trying to convey based on the sources used, the blurbs on the back of the book, and the metadata presented by the publisher, but the nature of these collages mostly just causes confusion and distraction.

In “Letter to Chow Mo-Wan,” the music is a bit clearer, but it really doesn’t add anything meaningful to the piece. According to Liu’s notes, this frankenpo is a conglomeration of a 20-year-old Chinese screenplay, the violin part of a Japanese song from 2016, music from a 20-year-old Chinese album, and quotes from 20th century queer theorist Eve Sedgwick, plus some gendered Japanese words (95). While there are poetic phrases in this piece, like “the caress / is not a simple stroking; it is a shaping” and “We are fool things …, precisely alive, mountainous” (64), there are just too many things going into this piece for anything to come out of it without a lot of research.

As a poet who is also a piano and guitar player, a student of the Japanese language (with a little knowledge of Chinese), a budding screenwriter, and an eager consumer of pop culture via books and movies, I was really hoping for more from this book. Liu should be credited for the few poems that do land, such as: “She’s People! 10 Apologies” (a kind of #MeToo frankenpo of “faux-apologies” from real celebrities, Sawako Nakayasu says in her blurb); “Portrait of Grandfather as a Robot Cowboy” (a four-stanza pantoum with a line of Japanese, and “I like this one” written in my handwriting in the margin); and “Dear I Ching, How Does HeteroPatriarchy Live on Through Me?” (which incorporates clever use of the multiple masculine Japanese versions of “you,” which vary in perceived politeness). However, the collection as a whole seems more like a visual art piece masquerading as an ode on Liu’s loves written in secret code. It’s difficult to imagine a reader that is better situated than me (on paper at least) to really appreciate this book, which begs the question, if I can’t make sense of it, who can? I did consider, thinking of Naoko Fujimoto’s “trans-sensory” graphic poetry book, Glyph (which over-stimulates me every time I try to “read” it), that there could be some Japanese-Chinese sensibility in collage poetry that just doesn’t resonate with American readers; maybe these poets are geniuses on a level I can’t comprehend, able to hold multiple modalities in their minds as they read and create (unlike me). But if Liu really wants to combat toxic masculinity, etc., is this esoteric collection of “poetry” really the best way to effect change? Or is Monsters I Have Been just Liu’s pursuit of personal catharsis?

Work Cited

Liu, Kenji C. Monsters I Have Been. Alice James Books, 2019.